The entire Court Order book collection of the Southampton County, Virginia Court from 1749 through the early 1880s has been digitalized. This includes 57,000 pages, involving approximately one million names. This information is free online at: www.wiki.familysearch.org/en/Southampton_County,_Virginia. This collection is a goldmine for African Americans tracing their ancestors who once lived in Southampton County. Many of the books that have been digitized were 300 to 700 pages. Court Order books from the 1700s to the end of the slave trade lists the names of Africans when they were first brought to the area, their ages, owner’s names, and in a few cases the ships on which they were brought over. Wills and estate settlements lists the names of slaves, descriptions and family relationships. If your ancestors came from Southampton County, Virginia, you must check out this collection. Thanks go to Southampton Circuit Court Clerk, Richard Francis, and the volunteers of the Brantley Association of America who undertook this huge project in 2009 and 2010.

Posts Tagged ‘runaway slaves’

Digitalization of Southampton County Virginia Records Opens New Doors for African American Research

Sunday, April 17th, 2011Runaway Slave Escapes to Freedom in Canada

Wednesday, January 19th, 2011Elijah Smyth or Smith was originally owned by Joseph L. D. Smith on his plantation in Florence, Alabama. When Joseph Smith died in 1837, Elijah was inherited by Smith’s minor daughter Jane, who later married George Augustine Washington of Wessyngton Plantation.

Between 1850 and 1860, Elijah Smyth made his escape from slavery in Alabama most likely using the Underground Railroad. He made it to freedom in Buxton, Canada. Buxton, was established in 1849 by the abolitionist Reverend William King, and was one of four settlements in Canada which offered refuge for fugitive slaves. Buxton was located between Lake Erie and the Great Western railway, and consisted of approximately 9,000 acres of land. The logging industry provided an income for most of its residents.

Reverend King had strict guidelines for the settlers: land could not be leased, and could only be purchased by African Americans for $2.50 per acres. Once the land was purchased it had to be held for ten years. Houses had to be built that were at least 24 x 18 x 12 feet with a porch, and picket fence and flower garden in front. The town had four churches, three schools, a hotel and its own post office. In 1860, Buxton’s population was its largest with about 700 residents.

Elijah Smyth was literate. Since educating slaves was forbidden by law in Alabama, he probably was educated at the Buxton school.

Between 1850 and 1860, Elijah Smyth wrote a letter to Jane Smith’s aunt, Anne Pope. He sent the letter from Buxton, Canada.

Mrs. Pope,

Will you be so kind as I do not know who my young Mrs. is married to or where she lives. The least she will take for my papers of liberty as I am ready to pay a reasonable price. It is better for her to get a half loaf than no bread. If she will take a reasonable price write to me and then I will write to you and let you know what day to have a man in Detroit with my papers and will send the money by a friend to meet him. Be so kind as to write to me in haste.

No more but kindness,

Yours truly Elijah Smyth

[Washington Family Papers]

In the letter Elijah Smyth offered to purchase his freedom. It is unknown why he made the offer since he was already free. He might have wanted to purchase the freedom of other family members who were still enslaved. It also is not known whether Jane Smith responded to his letter or accepted his offer.

Slave Life On Southern Plantations

Saturday, October 17th, 2009Enslaved African Americans on Wessyngton Plantation worked under a task system. The plantation owner assigned a task to each individual. Once the task was completed the slave was free to work on his own crops of tobacco if he chose to do so. The owner usually assigned tasks that would take the entire day to complete. However, some of the fastest workers were able to complete the assigned tasks and work for themselves. The slaves were not required to work on Sunday and were off half days on Saturdays. Many of the slaves used this time to cultivate their own crops. The task system required less supervision by overseers than gang labor and gave slaves more control of their time.

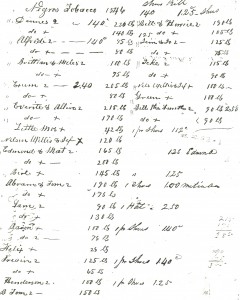

The owner kept a list of how much tobacco each person raised and paid them after the crops were sold in New Orleans. The slaves used the money from the sale of the crops to purchase various items not provided by the plantation owner. The document above lists the names of men on Wessyngton Plantation in 1846 who raised their own crops and the items they purchased for their families.

Runaway Slaves During the Civil War

Wednesday, October 14th, 2009

President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, issued September 22, 1862, declared freedom to slaves in the confederate states that did not return to the control of the Union by January 1, 1863. It did not free slaves from the border states Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, and Tennessee. Many slaves from these states, however, were already free by this time due to self-emancipation─running away or being abandoned by their owners.

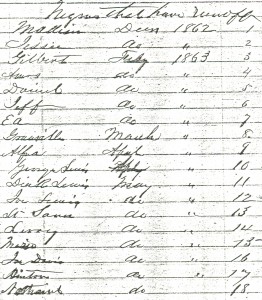

George A. Washington realized that his slaves would soon be tempted to leave his plantation Wessyngton. At the same time the Union Army was recruiting black soldiers, George made an offer to hire some of his slaves for a rate of $10 per month. From February through May 1863, twenty-four men agreed to stay on the plantation and work for the offered $10 per month. Of those twenty-four, however; eighteen left within a few months. The men had worked on the plantation all their lives and no doubt wanted to see what the outside world had to offer and to taste freedom. The men must have seen the offered salary as an attempt to keep them on the plantation. The above document lists the eighteen individuals who ran away from Wessyngton Plantation from 1862-1863.

Using Colonial Records to Trace African American Genealogy

Friday, July 24th, 2009

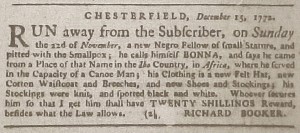

Virginia Gazette, Williamsburg, December 24, 1772

Chesterfield, December 15, 1772. Run away from the Subscriber, on Sunday the 22d of November, a new Negro Fellow of small Stature, and pitted with the Smallpox; he calls himself BONNA, and says he came from a Place of that Name in the Ibo Country, in Africa, where he served in the Capacity of a Canoe Man; his Clothing is a new Felt Hat, new Cotton Waistcoat and Breeches, and new Shoes and Stockings; his Stockings were knit, and spotted black and white. Whoever secures him so that I get him shall have TWENTY SHILLINGS reward, besides what the Law allows.

Richard Booker

A great source of tracing early African and African American ancestors is the Virginia Gazette. Slave owners ran ads describing in great detail their runaway slaves, apprentices and indentured servants. Many of these ads list native Africans, their ethnicities, country of origins, their owners, how long they had been in the colonies, and the ships they came on. These records are online at http://etext.virginia.edu/subjects/runaways/1740s.html.

Runaways and Rebels on Wessyngton Plantation

Thursday, June 18th, 2009

Wessyngton Runaways and Rebels

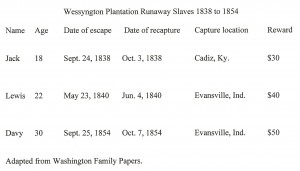

Enslaved African Americans used various forms of resistance against the institution of slavery. Some used passive forms of resistance such as pretending to be ill, secretly destroying tools, and work slow downs. Others used more drastic measures such as physical violence toward their enslavers and running away. Several men from Wessyngton Plantation escaped and made it to free territory. One slave Davy, ran away four times and was preparing to cross the Ohio River and go north to Canada when he was recaptured.