On November 20th I had the honor of delivering a presentation about my book The Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation to the entire fifth grade class at Gateview Elementary School in Portland, Tennessee. More than 100 students attended. Prior to my visit the students had studied the Civil War, which tied into my program. The students were very attentive and had many questions. Following the presentation many of the students expressed an interest in tracing their genealogy.

Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation Presented to Gateview Elementary School Students in Portland, Tennessee

November 30th, 2009Dred Scott Decision: Impact on African American Citizenship in the United States

November 24th, 2009

In 1847 an enslaved African American, Dred Scott, went to trial to sue for his freedom. This case, which later became known as Dred Scott v. Sanford, impacted the citizenship of all African Americans throughout the United States.

Dred Scott was born a slave in Southampton County, Virginia and was owned by Peter Blow. Peter Blow was the great-nephew of Colonel Michael Blow who owned my ancestors before they were brought to Wessyngton Plantation by Joseph Washington.

Scott was taken to Alabama by the Blow family and later to St. Louis. After Peter Blow’s death in 1832, Scott was bought by an army surgeon Dr. John Emerson who took him to Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory.

Scott’s stay in Illinois and Wisconsin, where slavery was prohibited, gave him the legal standing to make a claim for his freedom. The abolitionists encouraged him to sue for his freedom. The case and appeals took ten years. In March 1857, the United States Supreme Court declared that all blacks, slaves as well as free blacks, were not, and could never become, citizens of the United States.

The decision was a victory for southern slaveholders, while northerners were outraged at its outcome. The Dred Scott case influenced the nomination of Abraham Lincoln to the Republican Party and his election that led to the South’s secession from the Union and ultimately the freedom of all African Americans.

Peter Blow’s sons, who had grown up with Dred Scott, helped him pay the legal fees for his lengthy case. After the Supreme Court’s decision, they purchased Scott and his wife and then emancipated them.

Dred Scott died nine months later—a free man.

.

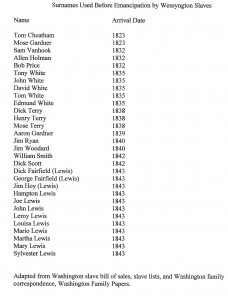

Use of Surnames Among African Americans Before Emanicaption

November 10th, 2009Slaves were usually known by their first names, especially on small farms with few slaves. Plantation owners rarely recorded their slaves with surnames unless they had several individuals with the same first names. For that reason the use of surnames by slaves was far more common on large plantations where more people were likely to have the same given names.

Due to Wessyngton Plantation having such a large enslaved population many African Americans are listed with their previous owners’ surnames as early as the 1820s.

Slave bills of sale and other documents in the Washington Family Papers collection details the origins of many of these African American families.

The list above documents the names African Americans on Wessyngton Plantation who used surnames prior to emancipation and the date of their arrival on the plantation.

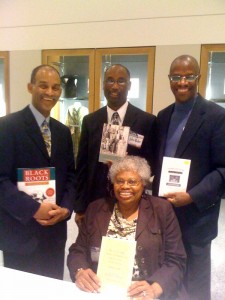

International Black Genealogy Summit in Ft. Wayne, Indiana

November 8th, 2009I just returned from a very exciting event—The first International Black Genealogy Summit held in Ft. Wayne, Indiana on October 29-31, 2009. Several hundred people participated. Throughout the conference I shared my research experience with genealogists. It was wonderful to speak with many people who had already read my book. The give and take of ideas illustrates that we are just at the beginning of a long and interesting journey to learn about our roots.

At the Meet the Authors event everyone could talk to the authors of books related to African American genealogy. The authors posed together for this photo. (L-R) Tony Burroughs who wrote Black Roots: A Beginners Guide To Tracing the African American Family Tree; myself; Tim Pinnick, author of Finding and Using African American Newspapers; and (Seated) Frazine Taylor, with her book Researching African American Genealogy in Alabama.

White Sharecroppers on Southern Plantations

November 6th, 2009After the Civil War several former Wessyngton slaves remained on the plantation. Others moved to Nashville, to the north, surrounding counties and some purchased their own farms.

When the former slaves left the area many white farmers and African Americans came to Wessyngton Plantation and became sharecroppers and resided in the former slave cabins.

Under the sharecropping system, the landowner received two thirds of the crop and the tenant or sharecropper only received one third of the crop. The sharecropper was provided a house, mules, land, seed and fetilizer. They raised crops of tobacco, corn, wheat and rye.

African American and white sharecroppers continued farming on Wessyngton Plantation until the property was sold by the Washington family in 1983 nearly 200 years after the plantation was founded.

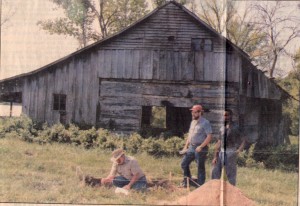

Slave Descendant Walks in Ancestors’ Footsteps on Wessyngton Plantation

November 2nd, 2009In 1991, I had an opportunity that few historians or genealogists ever have; to literally walk in your ancestors’ footsteps. In 1989 I was approached by the president of the Bloomington-Normal black history Project and director of the Midwestern archaeological research Center, about the potential investigations of the salve cabin area on Wessyngton Plantation to get an interpretation of slave life there. Similar digs have been conducted at the Hermitage, Mt. Vernon, and Monticello.

The actual digging at Wessyngton did not start until 1991. The thought of actually walking in my ancestors’ footsteps and holding objects they used in their everyday lives one hundred years earlier was surreal to me. Three sections of the slave cabin area were selected for exploration. One site was where the cabin of my great-great-grandparents Emanuel and Henny Washington once stood.

The dig yielded fragments of pottery and dishes used by my ancestors as well as coins and arrowheads made by Native Americans.

The photograph above shows the site of the archaeological dig on Wessyngton Plantation where my ancestors once lived.

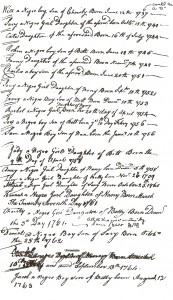

Slave Owner’s Family Bible Documents Slave Births During the 1700s

October 26th, 2009Slave owners kept detailed records of their slaves’ births, and deaths, and purchases; although many of them have not survived. They often recorded these events in their family bibles along with information on their own families.

The 1715 Blow family bible records the births of slaves owned by the Blows of Sussex, and Southampton counties in Virginia. Nineteen births of four mothers are recorded from 1737 to 1763 spanning three generations. This is a goldmine of information for African American research. Descendants of these slaves can be found searching other records in the Blow Family Papers in the Swem Library in Virginia.

Divorce Case of Former Slaves Reveals Family History

October 23rd, 2009Today divorce is very common, but in 1800s and early 1900s it was rarely heard of, especially among African Americans. In my research I found this extraordinary divorce case of two former slaves in Robertson County, Tennessee which detailed the history of their family.

Alford Pitt 1830-1900 and his wife Arry Fort Pitt 1836-1918 were married during slavery and had eleven children. Alford was a carpenter and later accumulated more than 500 acres of land. He had African American and white sharecroppers working his land.

In 1900, Arry filed for divorce from Alford stating that he had an affair with two black women and one white one. She stated that she had worked hard to help him amass everything they owned and she was entitled to half. Alford claimed that she had not helped him accumulate his wealth and felt since they married during slavery and never married after they were emancipated that she was not legally his wife and therefore not entitled to any of his property.

The divorce case put a great strain on the Pitt family, their friends and neighbors. Arry had more than fifty witnesses to prove her claims and Alford had nearly as many to support his. Half the children sided with their mother and the others their father.

Arry was represented in court by a family member of her former owners. In 1866, a law was passed in Tennessee which made all former slave marriages legal if the couple continued to live as man and wife.

The courts ordered Alford to give Arry 100 acres of land, $1,000, a horse and buggy and other livestock. Shortly after the verdict Alford died from complications of a cold that he caught from walking to court in bad weather.

Some of the Pitt property is still owned by their direct descendants. A street that runs through the property bears the family name.

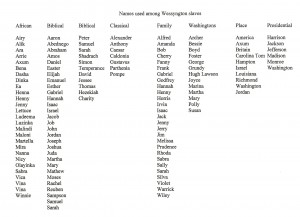

Sources of African American Names During Slavery

October 20th, 2009African Americans got their given or first names from various sources during the slavery. Some of them used African “day names” such as Cudjo, Mingo, and Cuffee, denoting the day of the week on which they were born. Others used names from the Bible, classical names, place names, names of plantation owner’s families, famous individuals like the presidents and their own family members.

The document above lists various sources of names of individuals enslaved on Wessyngton Plantation from 1796 to 1865.